When I was at Co-op Department Store in Derby city centre, selling kettles and toasters to regulars and chatting with those who simply wanted someone to speak to as they headed into town for their daily or weekly outing, often popping up like clockwork, I learned something that's stuck with me: the best moments happen when you help someone discover something for themselves, rather than just telling them what to buy.

That elderly gentleman who named his George Foreman kettle and toaster didn't need me to sell him anything. He needed someone to care enough to make the moment memorable. That's what leadership feels like to me, too. Not telling people what to do, but creating the conditions where they can figure it out themselves, and being there when they need a hand.

For over 20 years, I've learned that the best design work isn't just about what you deliver. It's about what you leave behind - the people you've helped grow, the practices that stick after you've moved on, the conversations you've changed.

This is what that looks like in practice.

Growing Others

I've always believed that talent shows up in unexpected places. You just have to be looking for it.

Spotting Promise Where Others Don't

At Next, I noticed two colleagues in Customer Services who had something special - Sonal and Arslan. They understood customers in a way that's hard to teach, because they'd spent years listening to frustrations, questions, and needs on the frontline. When the opportunity came to bring them into the Mobile UX team as Business Analysts, I lobbied for it.

As the most senior designer on the team, I took it upon myself to help them build the UX acumen they'd need. They already had the superpower - deep customer knowledge - they just needed the frameworks and confidence to translate that into design decisions.

We worked together on identifying opportunities, framing problems, and representing the Voice of the Customer in conversations with the wider E-Commerce department. Watching them grow from "I'm not sure I belong here" to confidently advocating for customers in senior meetings was one of the most rewarding parts of my time at Next.

They didn't need to become designers. They needed to become the bridge between what customers were telling us on the phones and what we were building on screens. That's leadership - knowing what someone can become, not just what they are today.

Mentoring Through Making, Not Mandating

At Funky Pigeon, I worked with two Junior UX Designers - Aneesa and Corin. Both were brilliant visual designers, quick in Figma, great eye for aesthetics. But they'd picked up some habits in previous roles that would hold them back as they progressed.

They'd copy screenshots and edit over them instead of designing from components. They'd jump straight into high-fidelity UI without thinking about the user first. And their Figma files? Let's just say collaboration was... challenging.

I could've pulled rank, told them to do it differently. But that's not how people learn. Instead, I designed alongside them, left inline comments in their work asynchronously, and gave in-person feedback that helped them see why reusability mattered, not just that it did.

"If I need to update this design next week, or if someone else needs to pick it up, how easy will it be to understand what's going on?"

Within a few months, both had shifted. Not because I'd forced them to change, but because they'd realised it themselves. That's the difference between compliance and capability.

The bigger challenge was getting them to think like UX designers, not just UI designers. Both were quiet by nature - something I could relate to from my early career. They'd design beautiful interfaces, but sometimes struggled to articulate the why behind their decisions, especially to senior stakeholders who didn't understand design.

So I stepped in. Not to take over, but to translate. To focus on the commercial outcomes their designs would deliver, rather than waffling about methodologies and thought processes that would lose the room.

Sometimes the best mentorship is giving someone air cover while they find their voice.

Both Aneesa and Corin have gone on to do great things. And they've told me, since moving on, how much those small moments of support mattered. That's the thing about mentorship - you don't always know the impact you're having at the time.

It's Not Just Junior Designers

Throughout my career, I've had colleagues reach out - Product Managers, Developers, peers at my level - wanting to understand UX better. Wanting to know how to run better research, how to interpret analytics, how to push back on stakeholders without burning bridges.

I've always believed that if someone's curious and willing to learn, it's worth sharing what you know. The best teams aren't the ones where the UX person is the only one who cares about users. They're the ones where everyone does.

Some of the most meaningful messages I've received have been from colleagues years later, thanking me for investing time when others didn't. For explaining things without making them feel stupid. For treating them like equals, even when I had more experience.

Rising tides lift all boats. The better everyone around you gets, the better the work becomes.

Establishing Practices That Stuck

One of the most satisfying parts of my career hasn't been the projects I've delivered. It's been the things that kept going after I left - the practices that became "just how we do things here."

Making Design Visible to Everyone

At Next, I'd noticed something fascinating in the Customer Services building at Head Office. All four walls were covered in writing - literally floor to ceiling. They used special paint that allowed CS agents to scribble common pain points, friction, worries, issues, and other incredibly helpful insights gleaned from telephone calls, emails, live chat, Trustpilot feedback, app reviews - every channel where customers were telling us what wasn't working.

It was primarily to help one another. A living, breathing knowledge base that anyone could learn from.

But as a UX Designer with a vested interest in user research, it was a gold mine.

I used to take myself off there for hours at a time, just reading the notes, making my own, mentally tallying up the recurrences to draw common themes. It was research happening in real-time, written by the people closest to customer frustrations. Some of the best insights I ever found came from those walls, not from formal research sessions.

It got me thinking: if making knowledge visible worked for Customer Services, why weren't we doing the same thing in our Leicester-based offices? We talked endlessly about omnichannel experience design, about the impact of visual merchandising in shop windows and store layouts - especially when I worked on an exploratory project around the feasibility of using beacons in-store. We understood that placement matters. That what you see changes how you think.

So I started putting our work up on the walls in high-traffic areas - near the coffee shop, by the staff restaurant, anywhere people naturally walked past.

Competitor analyses. Research findings. Wireframes. Even controversial ideas we were testing.

It wasn't about showing off. It was about starting conversations. About demystifying what the Mobile UX team did. About inviting people who weren't designers to have an opinion, because sometimes the best insights come from people who aren't in the weeds every day - just like those CS agents taught me.

Our Head of UX, Rich, told me one day that Simon Wolfson - the CEO - had stopped to look at one of our gallery walls and asked questions about it. That's when I knew it was working.

Other teams started doing it, too. The newly-formed User Research team adopted the practice. Design-focused teams across the business followed suit. What started as me borrowing an idea from Customer Services became part of Next's culture.

I didn't set out to change how the company operated. I just wanted people to see what we were working on. But that's how culture shifts, isn't it? Small things that catch on because they make sense - and because they're borrowed from people who've already figured out what works.

Creating the Blueprint for New Teams

My burger menu A/B testing work didn't just save £135m. It proved to Next's leadership that rigorous experimentation could protect growth and challenge assumptions.

About a year later, the business set up a dedicated Optimisation team to run experiments at scale. I wasn't invited to join - my focus was on innovation, and I became a founding member of the new Innovation squad instead - but I'd helped build the case for why that team needed to exist.

I shared everything I'd learned with Bijal, formerly of the Personalisation team, who went on to plan and run experiments for years. My methodology became the foundation for how Next approached testing going forward.

Around the same time, a User Research team was established. I was offered the opportunity to lead it, but turned it down after we couldn't agree on compensation. Even so, I worked closely with colleagues who were learning research on the job.

Alanta, especially, stands out. She came from a graphic design and UI background but wanted to move into research. I spent time with her, invited her to watch user interviews (in-person and remote), sharing approaches to remote testing, competitor benchmarking, translating analytics into insights - the foundational skills you need when you're making that transition.

She took to it quickly. And watching her confidence grow, knowing I'd played even a small part in that, felt as good as delivering any project.

Sharing What Works, Even When You're Not in the Room

I've always believed that the best leaders make themselves a bit redundant. Not in a "you're not needed" way, but in a "the team can carry on without you because you've shared what you know" way.

When I moved into the Innovation squad at Next, I didn't hoard the knowledge I'd built up. I worked with my colleague Jon, a Senior UI Designer in the My Account and Checkout UX team. Jon and I just clicked - we were perfectly matched.

I brought extensive knowledge of browse and shop journeys across apps and mobile web. Jon brought deep expertise in My Account, checkout flows, and all the legal and compliance intricacies of Next's Credit offering. Together, we documented processes, shared templates, and ran informal sessions to walk people through how we'd approached problems.

Some of the ideas we came up with during ad-hoc discovery sessions - away from our desks, just brainstorming - were so far ahead of the game.

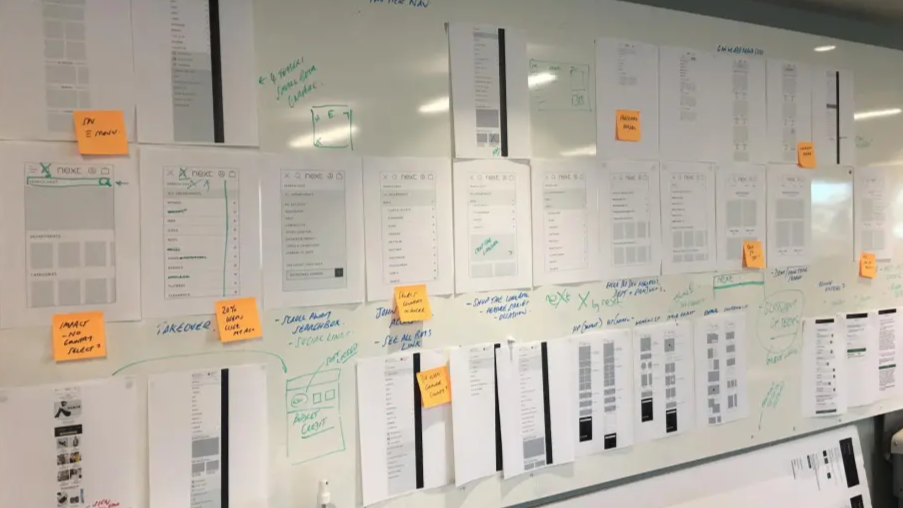

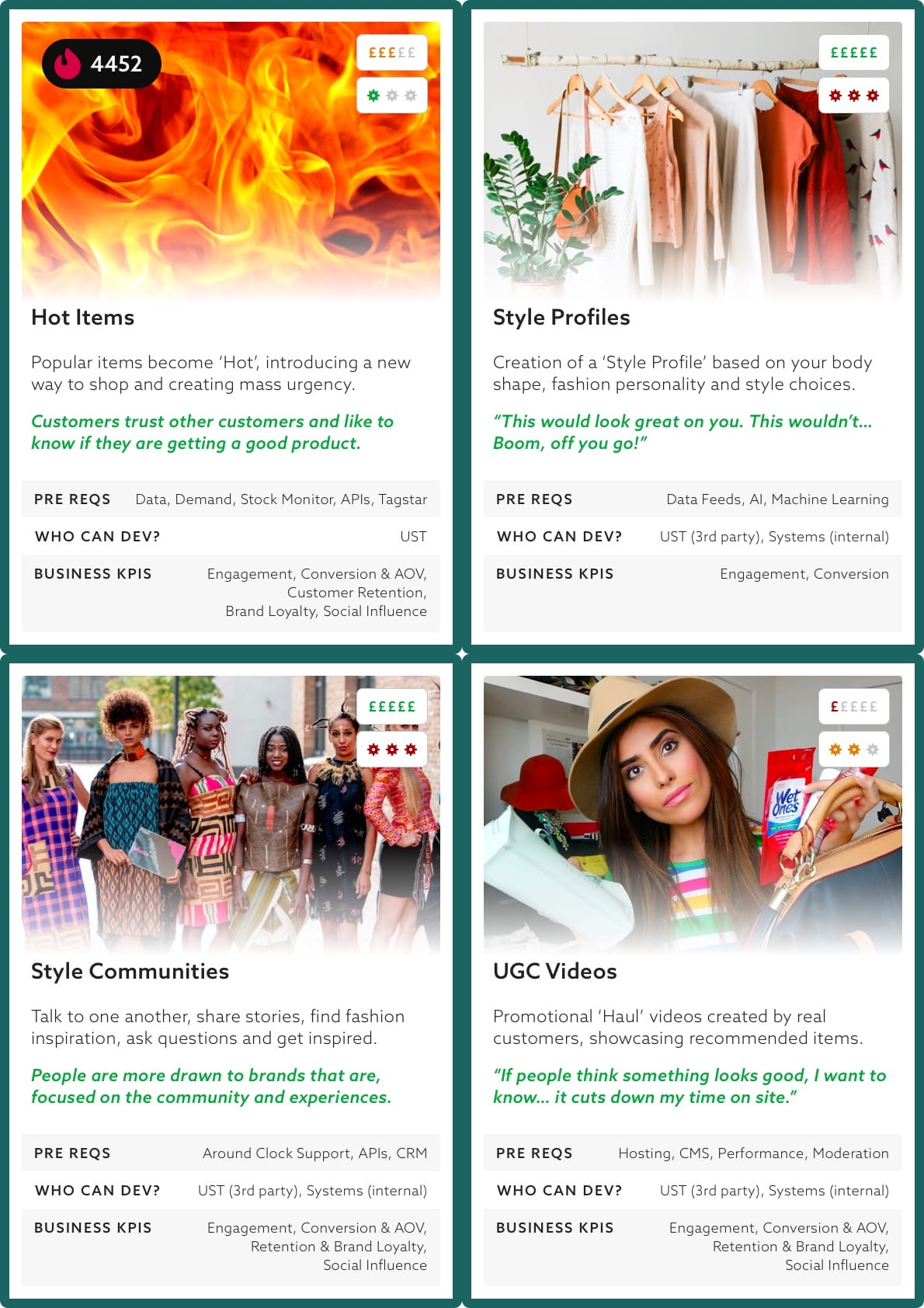

A "Capsule Collection" feature to help price-conscious shoppers overhaul their wardrobe for the upcoming season, demonstrating how to mix and match just a few essential items to create a plethora of different looks.

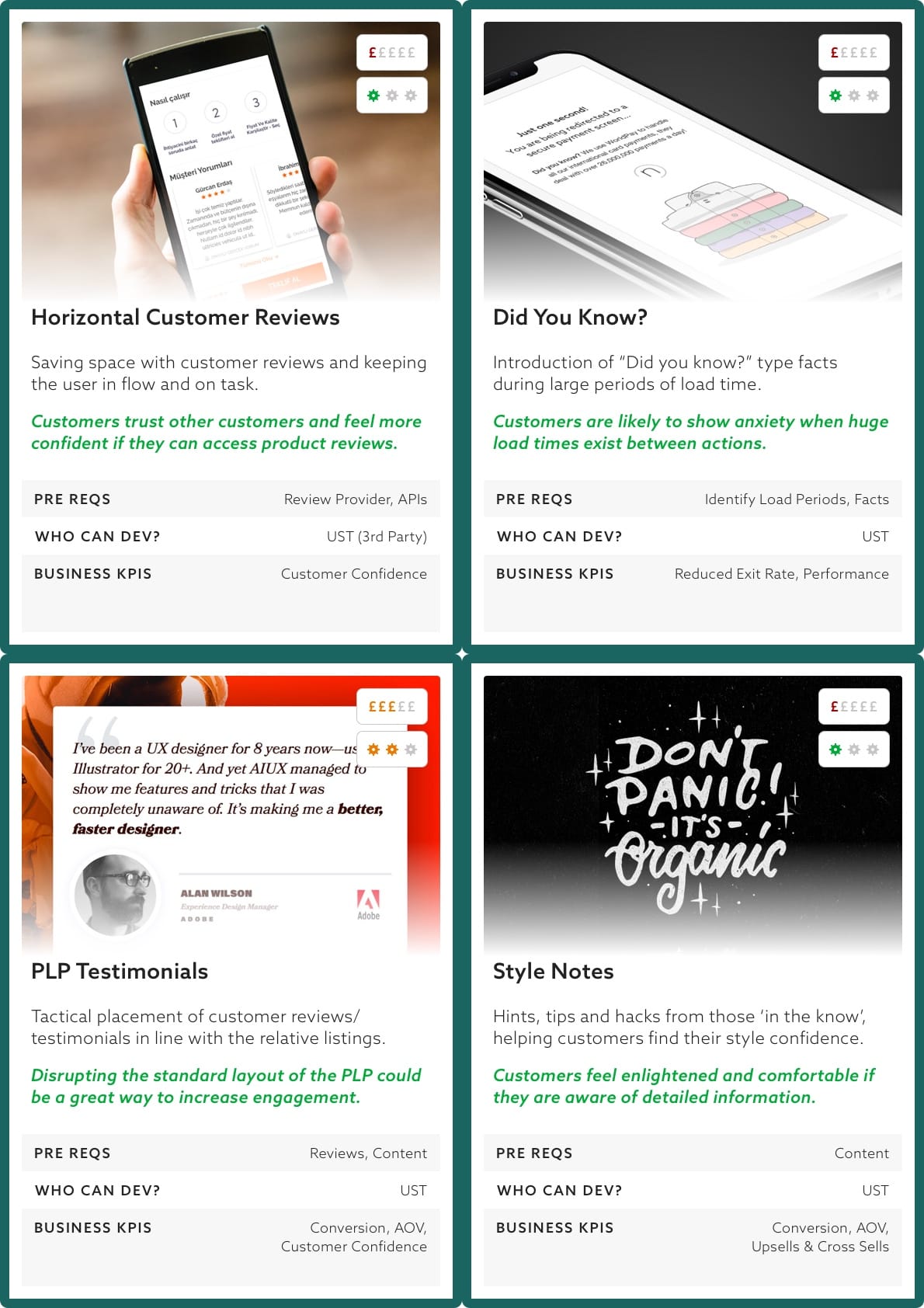

The "Drop a Hint" idea allowed shoppers to do exactly that - drop a hint to a loved one to let them know they'd like something for their birthday, or other such occasion - ideal for the individual in your life that has no idea what to buy you or for those who others see as hard-to-buy for.

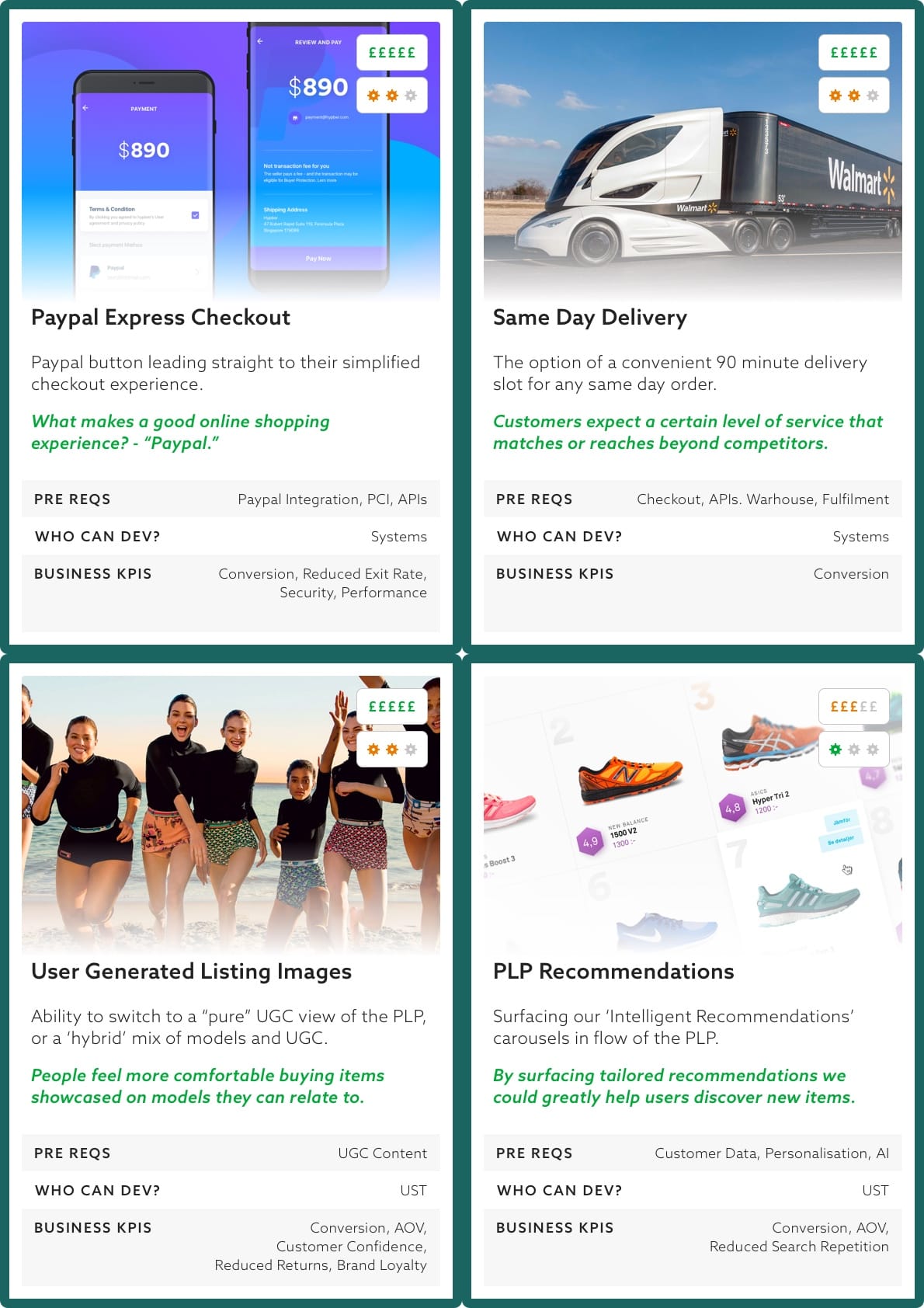

Even a "Showroom" feature to allow shoppers to share their favourite items, ahead of inviting their friends and family to offer their honest opinions, through "liking", commenting, and getting real feedback.

We came up with over 100 ideas, based on past learnings and insights gleaned about our customers.

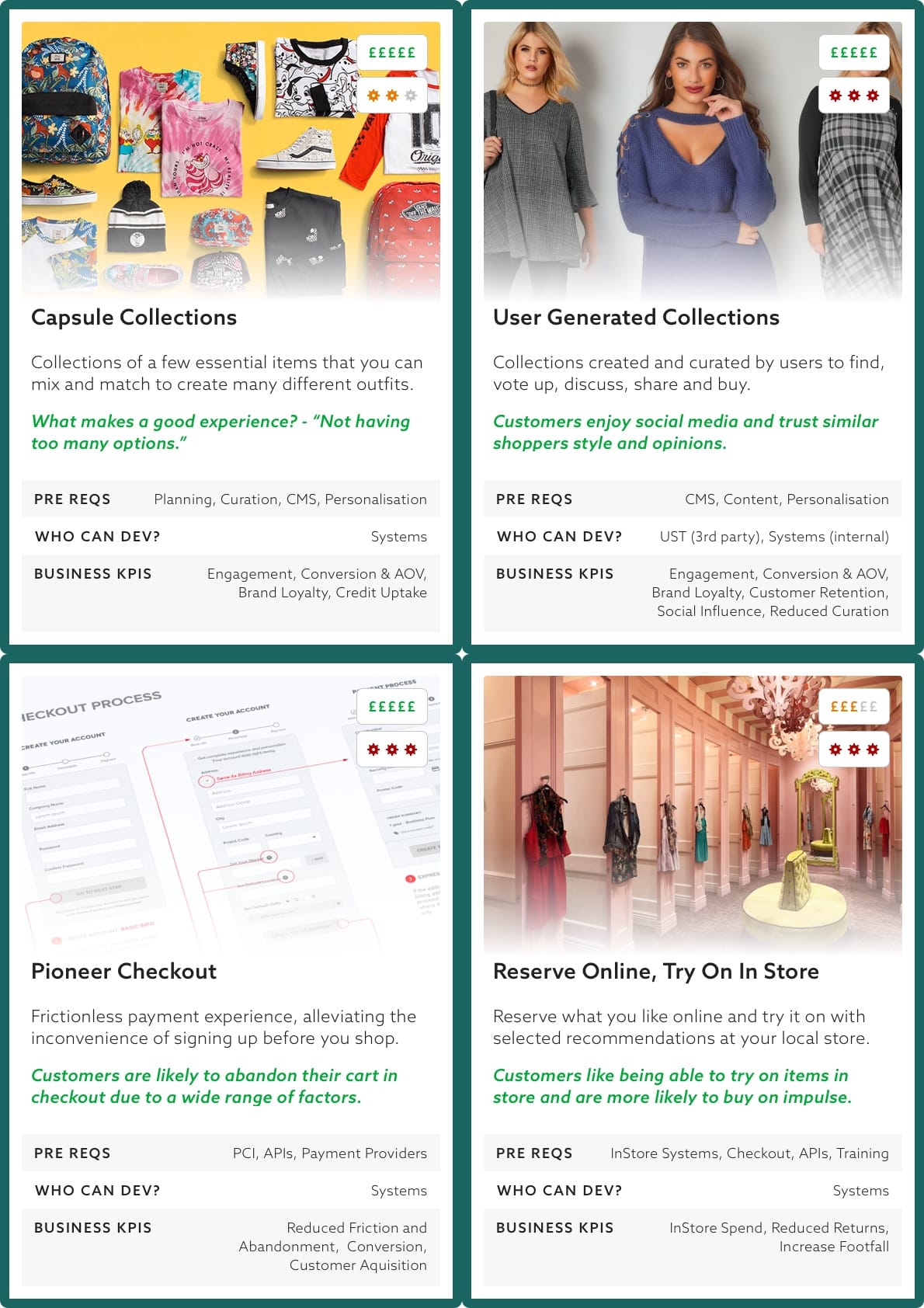

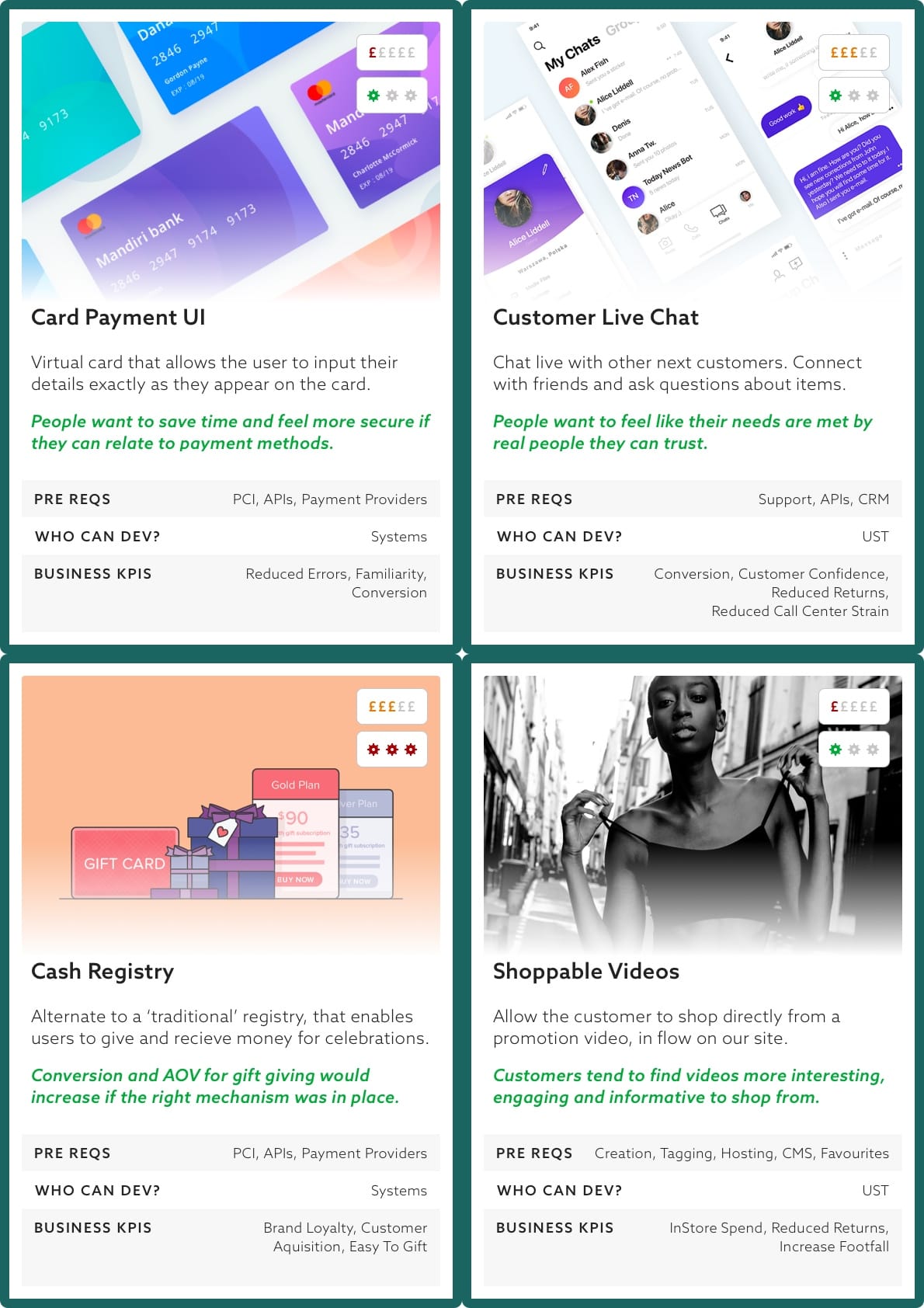

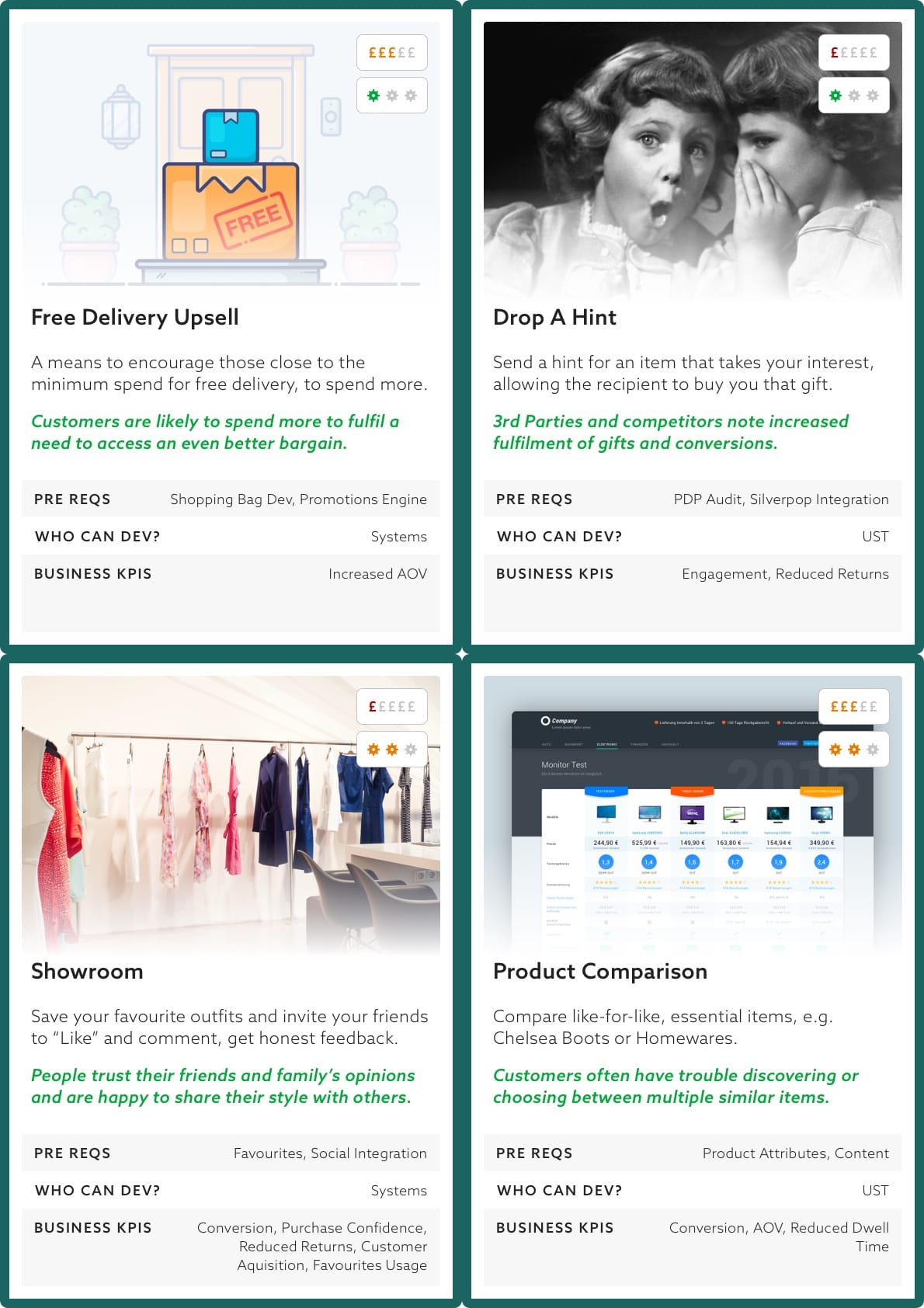

Both being Pokemon enthusiasts, we then came up with the idea of presenting these ideas as Pokemon-style trading cards, featuring a visual depicting the idea, the idea name, a one-line pitch/description of it, another line to demonstrate what feedback led to it being a value proposition, and then finally, a section detailing prerequisites (things that need to be in place to deliver such a solution), which internal team (we had many dev specialist teams) would be best placed to build it, and most importantly, what KPIs it targeted, e.g. conversion, purchase frequency, reducing returns, customer acquisition, etc. We also detailed the potential revenue gain and the estimated dev effort, in the top-right hand corner of each card, using a simple visual scale.

Unfortunately, the individual who headed up our Innovation Team shut us down, stifling our creative thinking because they felt it was "too risky" to present trading cards to the Head of Ecommerce. This was one of the reasons Jon and I both, very soon later, departed Next.

Because if you're the only person who knows how to do something, you're not a leader. You're a bottleneck.

Pokemon-style trading cards for innovation ideas at Next. Each card showed the concept, customer insight, prerequisites, which team could build it, KPIs targeted, revenue potential, and dev effort - making complex proposals instantly scannable.

Influencing Through Evidence, Not Hierarchy

I've never been the most senior person in the room, despite always being the most senior UX professional in every team I've worked in. And for most of my career, I didn't have direct reports or a Director title to lean on when I needed people to listen.

What I've learned is that influence doesn't come from your job title. It comes from the quality of your argument, the strength of your evidence, and your willingness to have uncomfortable conversations when everyone else wants to take the easy route.

The £135m Conversation

The burger menu pushback at Next wasn't about being right. It was about building a case that gave the team - and leadership - confidence to challenge what everyone else in the industry was doing.

I ran 70+ competitor analyses. I worked with data scientists to design rigorous A/B tests. I turned office walls into galleries so people could see the evidence for themselves, not just take my word for it.

When the results came in, they were undeniable. But even before that, I'd already done the hard work of bringing people along. Of showing, not telling. Of making it safe to question the trend, because the evidence supported us.

After we made the call to stick with the Snail Trail navigation, and the business saw the impact - £135m protected, 9.1% sales drop avoided - it changed how leadership listened to design input going forward.

Not because I'd won an argument. But because we'd proven that evidence-based pushback protects growth, and by me saying "no," rather than blindly accepting what I was asked to do by the Head of Ecommerce, and in turn, the Head of UX.

That's the kind of influence I care about. The kind that outlasts any single project.

Being the Voice for Customers When It's Uncomfortable

I've always believed we should champion the person who actually pays the bills - even when it's not the easiest route for the business.

There are always plenty of people in the room fighting for commercial outcomes. Revenue targets, cost savings, operational efficiency. All important.

But someone needs to be the voice asking: "Is this actually better for the customer? Or just easier for us?"

I've had those conversations more times than I can count. With Product Managers who wanted to cut a feature to hit a deadline. With Commercial teams who wanted to prioritise upsells over usability. With leadership who wanted to follow a trend because it was "industry best practice."

Sometimes I've won. Sometimes I've lost. But I've never regretted being the person who asked the question.

At Funky Pigeon, when Aneesa and Corin struggled to defend their work in senior meetings, I stepped in. Not because they weren't capable, but because they were still finding their voice, and I could see the conversation slipping away from what mattered.

I'd refocus the discussion on outcomes. On what this design would help customers do. On the commercial upside, not the methodological purity.

Because influence isn't about winning arguments. It's about making sure the right voices are heard, even if they're not the loudest ones in the room.

None of this shows up on a project timeline or a delivery roadmap. You can't put it in a quarterly business review or measure it in a sprint.

But it's the work that matters most to me.

Because design leadership isn't just about what you deliver. It's about what you leave behind. The people who are better because you worked with them. The practices that stuck because they made sense. The conversations that shifted because someone was willing to ask uncomfortable questions.

That's the kind of leader I want to be. Not the one with the biggest title or the longest feature list, but the one people remember because I helped them become the best version of themselves.

If that sounds like the kind of leader your team needs, let's talk.